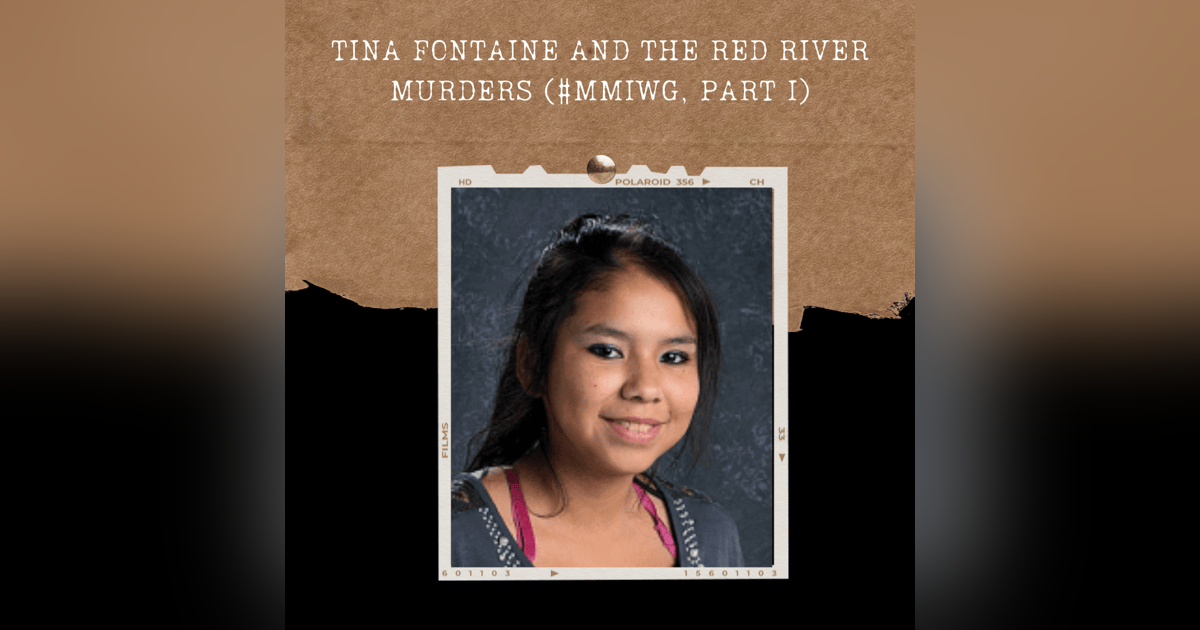

S02E07: TINA FONTAINE AND THE RED RIVER MURDERS (#MMIWG, PART I)

There are hundreds of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls across Canada, and these are just some of their stories.

In part 1 of a special 4-part miniseries, we will be covering the stories of various missing and murdered Indigenous women across the country and exploring the history and circumstances that has lead to this national crisis.

This week, Katie provides a brief history on the residential school system in Canada and how the deep trauma caused by these schools has lead to the national crisis we're seeing today. Also, she tells the story of Tina Fontaine- a fifteen-year-old First Nations girl who went missing in the summer of 2014 in Winnipeg , Manitoba. The investigation into her disappearance and the eventual discovery of her body in the Red River ignited public outcry and renewed demands for a national inquiry into the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women across Canada. However, Tina's body wasn't the only one found in that river... Sparking renewed public interest, this case is credited with bringing the issue back into the public consciousness.

EPISODE RESOURCES:

Why are Indigenous women missing in Canada?:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m2Cen4GyFjE

Why Canada is mourning the deaths of hundreds of children:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-57325653

Red River Woman, Joanna Jolly, BBC News:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-dc75304f-e77c-4125-aacf-83e7714a5840

Fontaine's death puts focus on missing, murdered women:

https://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/fontaines-death-puts-focus-on-missing-murdered-aboriginal-women/

Man acquitted of killing Tina Fontaine arrested in Ottawa:

https://www.aptnnews.ca/national-news/man-acquitted-of-killing-tina-fontaine-arrested-in-ottawa/

Daughter of Drag the Red co-founder will help keep search of Red River alive after her father's death.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/drag-the-red-co-founder-kyle-kematch-death-daughter-1.6165291

Volunteers find teeth by the Red River, Winnipeg police never show up to investigate.

https://www.aptnnews.ca/national-news/volunteers-find-teeth-by-the-red-river-winnipeg-police-never-show-up-to-investigate/

Volunteers find bones after dragging Winnipeg's Red River

https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/volunteers-find-bones-after-dragging-winnipeg-s-red-river-1.2011427

Canada’s Residential Schools Were a Horror:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/canadas-residential-schools-were-a-horror/

The Residential School System. Indigenous Foundations. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/residential-school-system-2020/

S02E07 Red River

Coming up on this episode of crime family: even before Tina's body was found in the Red River, there had been tragedy surrounding it. Police discovered a severed leg that had washed up on the shore of the Red River. And then five days after that, a man that was out for a walk, found an arm that had washed up on shore as well.

Volunteers found bones, the bottom of the river. They found a blood-stained pillowcase, a bloody carpet. And there was dentures found that were all handover over to the police. In 2015, they found teeth scattered along the shore. So these are all examples of like, they're finding things in this. So there are thousands of missing and murdered indigenous women across Canada that have not seen justice.

And these are just some of their stories that we're going to represent here.

You could have like a whole series of just cases of indigenous women.

This is not some like ancient history of our past. Like it starts then, but reaches into like modern times.

Hi everyone. Welcome to Crime Family. Today, I'm going to talk about one of Canada's most urgent and tragic realities.

Canada has a reputation of being a country full of really super nice and polite people. And while that may be true, it has a really dark history. And it's one that has largely been swept under the rug for over a century. It's a history of genocide of the indigenous people of our country.

When I think back to middle school and high school, social studies classes. Learning about the injustices against the indigenous people really does not stand out to me as a focus of any of those lessons. What do you guys remember learning about this subject in school?

I don't really remember learning about like the injustices of the indigenous community, really at all. We learned a little bit about like the history of some of the indigenous people in Nova Scotia itself, but we didn't learn like the dark side of history, residential school.

Maybe we touched on it, but definitely not to the extent that I think was required or that we needed.

Yeah. I have no recollection of ever learning about the injustice of indigenous people. All I remember learning about was like the way they hunted and the way they like lived their lives on the land. Like, I don't remember any of the dark side of that. Like, I don't remember learning anything about that.

Yeah. Like I remember like, I'm pretty sure I learned more about the dark side of it in the last couple of years than I ever did in school.

Yeah. Same with me.

Yeah. I know. I feel the same too. Like they really kind of shoved the European settlers down our throat. Like I know a ton about that. I mean, that's still a part of our history, but they like, without a doubt did not cover the history of indigenous people like they should have at all.

Yeah. Like, I'm pretty sure I learned a lot more about Christopher Columbus and that than I did about the indigenous people.

I know. Yeah. And like the ship Hector, like I came to Nova Scotia, like, oh my God. Like, yeah. I don't think there was more to learn about that. Like we know everything there is, but yeah, they kind of skipped over this, the indigenous history.

Okay. So I'm just going to go into a short history lesson about residential schools. And kind of the history of indigenous people in Canada. So residential schools were first opened in 1800's by the Canadian government and they were administered by the churches, largely the Catholic church. What led to the residential schools was the European settlers, you know, coming over, taking over the land. And they were, they believed that they were superior, that their civilization was kind of like the pinnacle of human achievement and they needed to basically teach the uncivilized quote, savages the European way of life. So according to an article written by Aaron Hanson, Daniel Gamez and Alexa Manuel for the indigenous foundations, from the University of British Columbia, the Canadian indigenous schools were designed after their American counterparts and they adopted the quote aggressive civilization example that the US had within their industrial schools for indigenous children. So I guess the US history could be pretty similar to Canadian history for indigenous children.

So the goal of these schools was to get them while they were young and to try and eliminate any trace of their indigenous roots. More than 150,000 children were forcibly taken from their parents, taken from their homes and they were made to live in these schools.

They weren't even allowed to speak their native language most of the time. And they were often physically punished if they did speak their language. I mean, these kids didn't know any other language. So it was like, they weren't really allowed to talk.

So the conditions in these schools were deplorable. They were underfunded. There was many children that went to class part-time and then the rest of the time they worked for the schools like girls did things like laundry and cleaning, while the boys did maintenance of the school and agriculture. Of course, all this was like involuntary work and it was unpaid. There was physical sexual and emotional abuse that ran ramped throughout the schools. And so did sickness amongst the kids that live with.

So astonishingly, these schools ran for like 150 years in Canada. And the last one wasn't closed until 1996, 1996!. Like that still blows my mind at how, you know, close the schools were like we were alive then. And they were still open.

Yeah. Yeah. So it's not like this is not some like ancient history of our past. Like it starts then, but reaches into like modern times more or less.

Yeah. It's, it's pretty sad. In May of 2021, the bodies of 215 indigenous children, some were as young as three years old were found at one of the largest decommissioned residential schools in Kamloops, BC. And they found these bodies using ground-penetrating radar.

So at the time that we're recording this there's over 1300 un-marked graves have been found at just four out of these 139schools across Canada. And according to Ian Mosby and Erin Millions for Scientific American, they quote that the official number of 4,120 students that were known to have died in the schools will end up being just a fraction of the actual total.

So all of these children went to these schools. They, and they just never came back. And a lot of them just had no explanations given to their family. They were just never seen again. So just, can you just imagine how horrible that would have been and how horrible it probably still is for a lot of these families?

So the Canadian government made a public apology in 2008. To the indigenous communities across Canada, but this does little to even begin to reconcile the ongoing impacts that indigenous communities across Canada are enduring. And quoting from the indigenous foundations the historic intergenerational and collective oppression of indigenous peoples continues to this day in the form of land disputes, over-incarceration, lack of housing, child apprehensions, systemic poverty, marginalization, and violence against indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBQQIA peoples and other critical issues, which neither begin nor end with residential schools, end quote.

So with all of that, this is kind of like the beginning of our four-episode mini-series that we're dedicating to the ongoing violence against indigenous women and girls in Canada. So there are thousands of missing and murdered indigenous women across Canada that have not seen justice. And these are just some of their stories that we're going to represent here.

So according to an article written by Joanna jolly for the BBC called Red River Woman. Aboriginal women are four times more likely to be murdered or go missing than other Canadian women. The first case I'm going to talk about is Tina Fontaine's case.. She is also known as the Red River woman. And her story is what kind of added enough fuel to the fire to get the country's attention on the epidemic of missing and murdered indigenous women in Canada.

So, although there were thousands of missing and murdered indigenous women before Tina Tina's murder in 2014, made headlines across Canada. In 2015 prime minister, Justin Trudeau announced a national inquiry into missing and murdered indigenous women following Tina's death. It just kind of woke up the rest of Canada that may not have been paying attention to this serious situation. May not have noticed it was going on. It just kind of shed a lot of light onto the situation, but it's sad that it had to be, you know, this little 15 year old girl to kind of wake Canada up, wake up Canada.

It actually blows my mind that it wasn't until 2014, that people started to investigate into like these missing indigenous women. Like it happened so long ago, like back when residential schools were still openness and like, it's, it's sad to me. Like it took them till 2014 for them to realize the seriousness of what was going on with the indigenous women. But then still today, like 2021, it's like everywhere now. It's kind of like a little bit too late.

Yeah. Like it took too long.

Like it's sad those bodies were found and it's sad about the residential schools, but like, it has been going on for like decades and it just breaks my heart that it took this long for anybody to pay attention.

Yeah. It's sad that they found those bodies. It's sad that there's that's it actually happened. And then it's sad that it took so long for, you know, everyone to wake up about this. Like even thinking about myself. I think I kind of got in tune to the situation was when Loretta Saunders was murdered and the only reason, not the only reason, but why I think why it kind of got my attention is because she went to St. Mary's University, which is where I graduated. So I kind of had that connection of, oh, this is super close to home. And so that's. Kind of where open my eyes, but yet it still took a while.

And I think, no, obviously after the discovery of all those bodies this year, obviously, it's much more like in the public consciousness, but still not even as much as I think is deserved considering the amount of women that are still missing the amount of, you know, people who, women who literally just disappeared and either no investigation was done or very little was done.

Um, and I do just want to say, I know I was going to bring this up at some point during this like four-part thing. I might as well say it now, but we're recording this episode around the same time. that's this whole, um, Gabby Petito cases happening. And that's a huge story. That's like, you know, basically making headlines all around, you know, the US and Canada and the world.

And I just think if even a fraction of attention that that case has gotten. Was given to some of these murdered and missing indigenous women in Canada. Like, just think of the effect that could have, or like how many cases could be solved or if, and as like when it's happening, not like 10 years later, but like, as it's happening, if we saw something like that for one of these women, like, just imagine what the case could have been, you know, a lot of these cases could have been solved.

So I just wanted to like, kind of say that it's crazy, that that case, which is just, you know, a young, white, blonde hair, blue eyes, girl. And not to say that that doesn't deserve attention because it does, but so it's not like I want to give that less attention. I think it deserves that attention, but all these other cases need to be given that same amount of attention.

And like, when we, when I was like doing my cases and like learning about other people's cases as well for this mini-series there wasn't a whole lot of information out there on like a lot of these women who went missing. A lot of them, they kind of just like the police didn't really dig deep or didn't really seem to care.

Cause it just there's like no information out there about hardly any of these women. And it's like nobody ever got justice or maybe some of them did, but a lot of them, their parents have passed on and never got justice for their family. What I really like. There's just so much injustice in this that happened to these people that like it's actually sickening to me.

Yeah. So kind of both your points there. I think Gabby case, I mean, that's only been unraveling for like a couple of weeks and there's already like YouTube videos with like millions of views that people are so interested in this. And then what Steph was saying, when you look at some of these, you type in some of these missing indigenous women and there's like a paragraph about them and they've been missing for decades or years, and you can't, there's nothing you like Google it and there's like an article and that's it.

Like you can't, there's nothing else about them. It is sad how unrepresented they are in the media.

Yeah. And that's why, you know, yeah. Like when we were looking at which cases we wanted to cover for this mini-series, like, it was hard to find one that would actually, unfortunately, that would fill an entire episode.

Cause some of them literally say this woman was last seen on this day and that's it. That's literally all there is. There's like barely any investigation. There's no other information. So that's really sad.

So back to Tina's case. Tina lived with her younger sister and her great aunt Thelma on an Aboriginal reserve, north of Winnipeg, Manitoba, and Tina was happy at school. She had lots of friends and she was the kind of person that would stand up for others when they were being bullied. She was kind of that person that people went to for kind of comfort and help.. She wants to be a social worker when she got out of school. So she was very much, you know, into helping people.

Things started to shift for Tina in a really big way when her biological father was murdered in a bar fight one night. It was really unexpected. So as can be expected, Tina really struggled with this. Like she was only 15 years old and her aunt could see that happiness in Tina is starting to fade away. So Tina began to have more and more contact with her biological mother who lived in Winnipeg.

They would kind of talk a lot more over the phone and Tina was continuing to get really good grades at school. And what you really wanted was to go visit her mom in Winnipeg. And so as a reward, her aunt allowed her to do this. And I think just kind of based on the timeline of everything that happened, it was kind of during her summer break.

So she was kind of planning on going for a couple of months. Tina's aunt gave her some money, gave her a phone card and told her to call her if she needed any help at all with anything, she was always there. Just call her. So Tina's visit with her mom really did not turn out the way that Tina was hoping. A lot of what happened while Tina was down in Winnipeg visiting her mom is largely unknown, but she would contact her younger sister saying that she had been beaten by her mom and her mom's boyfriend. And she would send pictures to her younger sister showing that she had bruises all over her and she would show or send pictures of her doing drugs. According to that Red River woman article, the last text that Tina sent to her sister was for her aunt and her aunt's husband. And it said, quote, tell mama and Papa I love them and miss them, but I'm not ready to go home end quote. So Tina was with her mom for about a month before she was reported missing and in a Dateline special broadcasting episode with Lauren Murphy Oats and Kylie Gray, they talked to Tina's great aunt Thelma.

Thelma tells them how one night after Tina was reported missing already, the police did find her and her name was flagged as missing and everything. She was intoxicated. She was obviously under age. She was only 15, but they said she looked even younger. Like she looked like she was around 12 and the police for whatever reasons, still like, just let her go.

And after that, she lost contact with everybody.. And just a couple of days after that on August 17th, 2014, her body was found in the Red River. It was wrapped up in what some sources say was a garbage bag. Some say it was a duvet, but it was weighted down by rocks and throw it in the river. Her body was in such a state of decomposition that it took investigators hours to determine that was even a female body that they had told them the River.

And it took hours after that for them to make a tentative identification. And according to Red River woman article, it was a tattoo of angel wings on the back that helped him discover that it was Tina's body. 16 months after her body was found, they arrested a man named Raymond Joseph Cormier. He was charged with second-degree murder on December 8th 2015, but he pleaded not guilty and he was actually acquitted. So Tina's murder has never been solved . Recently on March 16th, 2021, Raymond Cormier was arrested in Ottawa for allegedly breaking into several apartments. So he obviously has issues whether he committed this murder or not, but her murder is still unsolved.

So the Red River, which is where, you know, Tina's body was found, it runs through Winnipeg Manitoba. It's about 885 kilometers long and 255 kilometers are actually in Canada. The rest of it flows northward from Minnesota and North Dakota in the United States. And it flows through the Red River valley and it ends in lake Winnipeg.

Now the city of Winnipeg has a larger indigenous population than any other Canadian city. And it's known for its high murder rate and it has gained the nickname murder peg for its high rate of violence. There are many very remote indigenous communities that surrounded when a peg and these communities are almost like Canada's forgotten people.

These communities are full of poverty. They have very little resources. Some of the living conditions are terrible. Some families live in condemned houses with multiple families, all in one house. And so it's really common for teenagers, especially teenage girls to want to escape their living situations here.

And so they travel to the closest city, which is Winnipeg. And of course, once they get there, they don't have anything. They don't have any where to live. They don't have family, a lot of them. And at this point they're considered runaways by police. A lot of them get into sex work and really dangerous lifestyles, you know, drug abuse, alcohol.

And they become really easy prey for predators when they go missing, because their families really have no way of knowing that they've disappeared right away. And there's many, many reports of police not taking these cases as seriously as they should. And there's many accusations of racism in the police department, as apparently once the police hear that.

An indigenous person, they just considered a runaway and they lose interest right away. So they don't do as much investigating as they probably should. Especially since these are underage, you know, really vulnerable teenagers, teenage girls. So the Red River itself in Winnipeg is related to a number of indigenous cases.

While police were still investigating Tina's murder. Like back in the early days when it happened, another teenage indigenous girl was found on the banks of the Assiniboine River, which right before it connects to the Red River. So it's the same body of water. This girl's name was Rinelle Harper. She was found half naked, unconscious, and the temperature outside was minus three Celsius.

So that's like 27 degrees Fahrenheit. But police say that the low temperature actually helped keep her alive because when it's that cold, the body starts to slow down metabolism and it can start healing itself, of course, to a point until it gets too cold for too long. And then you freeze to death.

Rinelle actually did survive though. And her story was that she was out with friends and she was lured under an isolated bridge by two young men. And when they got her there alone, they sexually assaulted her and they physically attacked her. She ended up in the river, but she doesn't exactly know how she got in there.

She doesn't remember if she ran in there to get away from them or if they threw her in, but she does know that she made it to shore. And when she got there, they attacked her again. And then they just left her for dead. And those men that same night went on to sexually assault another woman as well. I don't know who these men were.

If they were caught, I feel like they were because they know that they attack somebody else, but there really isn't much out about that. And Rinelle waived her right to stay anonymous. And she spoke out about her case to try and help others that were victims of assault and murder. So even before Tina's body was found in the Red River, there had been tragedy surrounding it. In March of 2003, a 16-year-old girl named Felicia Solomon Osborne went to school one day, but she never returned home.

Her family put up missing persons posters. And this was another example that they felt the police really didn't do enough or anything to try and find her. Sadly three months after she went missing on June 11th, 2003, while conducting routine dock maintenance police discovered a severed leg that had washed up on the shore of the Red River.

And then five days after that, a man that was out for a walk found an arm that had washed up on shore as well. And they found that both of these limbs belong to Felicia and her murder is still unsolved as well. That's really all there is out there about these cases. There was another woman named Bernadette Smith and her friend, Kyle Kematch.

They believe that there's other women waiting to be found in the Red River and they've begun searching for themselves. They kind of drag the bottom of the river on their own searching for bodies. Bernadette's half sister Claudette Osborne was last seen in July of 2008. Maybe her sister could be in this river. The last time anyone heard from Claudette it was through phone messages that you'd left on answer machines that she'd left at four o'clock in the morning one day. Apparently, she had been bleeding really bad and she was being attacked by a man. And she was like calling everyone that she knew for help, but it's kind of weird. Apparently, she was using a calling card that had run out of credit. So it was days before anyone even got these messages. I'm not really sure how that works. That was like 2003 calling cards or weird, but needless to say it was too late and she's never been found either. Kyle's sister, so he's the Kyle Kematch who I just mentioned. His sister, Amber also went missing in 2010, never been found.

After Tina's body was found Kyle co-founded the foundation called Drag the Red. It's a volunteer foundation where they search and drag the bottom of the Red River looking for bodies and they just feel like they don't really have a lot of support from police. Police aren't doing this. It's kind of a volunteer community that has to do with themselves.

And according to CTV News in September of 2014, volunteers found bones at the bottom of the river. They found a blood-stained pillowcase, a bloody carpet, and there was dentures found that were all handed over to the police. In 2015, they found teeth scattered along the shore. So these are all examples of like they're finding things in the river.

Nothing has come out about who's DNA, whose bones, whose teeth these were, but they're, they're finding body parts in the river. So sadly Kyle, who was a co-founder of the organization, he passed away just since September 2nd, 2021. He was only 38. He unexpectedly passed away, but his daughter is going to help continue on with the work of Drag the Red. And it's just, I mean, it's really encouraging that these communities are coming together to solve this, but it's like, where are the police with these kind of things, right? Like they, maybe they are helping, maybe they're putting in some funding, but it just seems like it shouldn't come down to family members that are missing people that have to kind of go through this to find their family members.

What do you guys think so far?

I think it's really sad that volunteers were looking for these body parts. That kind of shows that the police just shoved it under the rug and didn't really seem to care. Like I don't, I don't, I just don't understand like the injustice of that.

Maybe they did not like probable cause. And they, you know, they can't just go looking everywhere somebody thinks there might be something.

Even if you found dentures or like something you can find DNA from that and can't you find out who these people were.

Yeah. And I mean, they handed all this stuff over to police, so I don't know if they, if they have been able to match them, nothing's I couldn't find anything that came out for positive IDs. So yeah, it's really sad.

I don't know. I just don't understand why, like these indigenous women are just getting such poor. Like there's no outcry, like nobody, like the police don't really seem to care about these, these women.

And it's just like, I don't know. I just, I don't know. I just don't understand. I don't even want to do my case. Like, we'll hear about that later, but when I do my case there's just nothing and nobody, nobody seemed to do anything about it. I'm just like why. That's my biggest question. Why aren't people doing anything about these women?

Yeah. And in another case, a woman named Jennifer Catcheway disappeared and she's not related to the Red River, but I mean her family, basically every year after the snow melts, they go out and search for her body. They dig through the landfills, they're digging through these mounds of dirt. They're digging through anything that they think someone would want to dump a body and it's them going out themselves with equipment and just shovels looking for bones of their daughter because they think the police have basically just, you know, written them off. And this family said that when they did first report her missing to the police, apparently the police were like, oh, you know, how old is she?

She had just turned 18. So there, and they knew that this was an indigenous family. And they said, oh, she's probably just out drinking, give her a week she'll come back. And that's kind of the attitude that everyone says. It's like all the police find out that it's indigenous. Oh, they're just out partying.

You know, they're probably out doing drugs and drunk and they're drunk. They'll come back in a week or so because there's that stigma, you know, that like indigenous people there, that's all they do is, you know, party and drink. And, and there is like addiction and alcohol issues that are in these communities because of kind of all this that has happened in the past, the systemic racism that still happening.

It's causing these larger, larger issues for these communities. And so as Winnipeg is just one of these examples where indigenous women are targeted for violence and murder because they are living on the margins of society. There was a man named Sean Lamb. He was dubbed a serial killer and he was convicted of killing two Aboriginal girls in Manitoba.

And he described them as quote, the perfect victims. Because as that Red River article explains, no one really seems to care if they go missing. So it was just easy to pick off these girls. And there's also the serial- have you guys ever heard of the serial killer Robert Pickton from Vancouver?

Yes, I have.

Me too.

Okay. Yeah. So I'm not going to go into it, but Robert Pickton. He was convicted of killing six women, but he was originally charged with 26 counts of murder. And he even said himself that he actually murdered 49 women and he wanted to make it an even 50, but he was caught before he was able to, but many of his victims were indigenous women from the downtown eastside of Vancouver, kind of living that dangerous lifestyle on the streets.

Like a lot of these bodies have never been found. There was just DNA from a lot of indigenous women at his gross house and farm. So.

He was the pig farmer, right?

Yeah. He was the pig farmer that, I mean, some people, some sources say that he fed some of the, his victims to his pigs. I'm not sure if that's true. What I've heard is that he kind of the remains of his victims he would kind of put them in with the bodies of slaughtered animals and bring them out to like the rendering farms so that everything was mixed together. There was no way to know what was. Maybe both are true, but like his story, he was just like a gross guy.

And like, he would just pick up these sex workers and obviously he just killed a lot of them and a lot of them are indigenous and the police didn't do a lot. This was like in the 1980s for like couple decades, he was doing this and the police were kind of not looking into it as much as they should have, because they were, again, these marginalized, you know, sex workers that lived on the street.

So it's just. But other sad situation. So you can definitely like feel the desperation of the situation just by these few cases that I've talked about, but there's hundreds, like even thousands across the country. If you go to cbc.ca/ missing and murdered, you can see the profiles of 250 of these cases.

They're still working on more. But that's what we were talking about before you click on one of these names and it's just like a paragraph or sometimes just a sentence about what happened to these people. These girls that are missing, some of them are murdered and just unsolved and there's nothing else to go on.

So, I mean, it really, isn't a problem. This is just one example. That's happening in Winnipeg, Manitoba, but it's across, it's across Canada and yeah, we're going to talk about more in our other upcoming episodes.

And a, and a lot of predators too. Like they know that they're more likely to get away with it if they target this community because they know the police are going to not be looking into these disappearances.

And they know, you know, I guess probably for a lot of like serial killers or you know murderers in general, they do prey on the vulnerable populations. You know, just think if you're, if you're someone who's trying to get away from, from the police and evade, the police, you know, it makes sense that you would target people who, you know, oh, it's going to be like 10 years before they even like start looking.

And then by that time, everything will be, you know, there'll be no evidence left. It makes it so much easier for these people to get away with it too.

Yeah. And I think that is why, you know, people can just get picked off. They're in these dangerous situations already, and they're living these lifestyles where they're maybe, you know, not checking in every day with their family because they're not living with their family.

Some of them they're hundreds of miles away from their actual family. So there's no way for them to know they're even this. And the ones that do have family close by, like there's their lifestyle is there'll be, they can be gone for weeks or months at a time and then come back. So, you know, they could be missing for months before people even really know that there is this other case that I was looking at and this woman had disappeared, but she'd kind of left her family.

Like that was her decision. She wanted to leave. She was only like 17 or 18. But anyway, she actually didn't get reported missing. Like if you guys think, how long do you think would be like an absurd amount of time before someone gets reported missing? Like just off the top of your head?

Like a couple of weeks? Probably.

I would say like a couple of weeks or two months maybe.

Okay. This person didn't get reported missing for 40 years. And like their family knew that she was out there somewhere. They just assumed that she, like, she just didn't have contact for 40 years. And finally, someone was like, probably something fucking happened to her.

40 years, even like.

Like, it seems ridiculous.

And it's like, they talk like, I mean, officially, whether like, yeah, let's file a missing persons report, like open a case, but they had talked to like maybe friends and family and even police about like, yeah, we're not really, really sure where she is. But we know that she doesn't really want to be found.

So it was kind of like, well, that's like, we know she wants to be gone, but they never, they knew she was not with them. Like they knew she was somewhere, but they just didn't actually report her missing for 40 years. And she hasn't been seen obviously for 40 years. So it's just kind of crazy.

But why after 40 years would you file a report? Like it doesn't really make sense to me. Like if she didn't want to be seen and nobody's ever heard from her, why take 40 years to be like, oh, maybe she's missing?

Probably cause it, you know, they still thought about it throughout all the years. Maybe they're just like, if they actually.

Someone sees her she's actually missing. Then they can report that they've seen her. Maybe she'll actually come forward and say, this is where I am. Like they should all be changed her name has a family..Like that's what they're, they're hoping that you changed your name, had a family of her own and just kind of started somewhere else.

And they're thinking maybe if they report her missing that she'll come forward. Someone sees her they'll report it where if they don't report her missing, no one is going to do that because they don't know.

But would the police even like investigate something that that's been 40 years missing? I feel like that's not something they would. I mean, they don't really do a lot of investigation with people who go missing like two weeks for indigenous people. But I'm just saying like 40 years of a long time, like, would they even open a case for that?

I don't know. I feel like they'd probably have to for the law, like someone reports the missing, they kind of opened it up, but whether they're going to like search for her until they find her, I doubt that.

Oh, I mean, some of her family thinks she's probably out there. A lot of them, you know, back of their mind probably thinks something happened to her early on. And just her body's just never been like identified even so. Yeah.

And it's crazy. Cause when you think about it, yeah, it's been 40 years. She could, you know, something could have happened to her.

She could have been killed, you know, the first year after she was not seen. So it'd been 39 years since she was alive. So, you know, what are the chances of actually. The police actually finding anything of substance 39 years later if they haven't already. But I mean, also too, maybe they did find like a lot of bodies do get, I mean, I don't know the process, but a lot of bodies do get fine and they can identify them.

And so they're just kind of known as Jane DOE or something. So like maybe she had been found, but she just hadn't been linked to that person before.

Yeah, exactly. She could have been one of those unknown bodies. And I think eventually they, you know, they buried them as a Jane DOE or something. So I don't know.

They probably, they just don't know. Anyway, it's just really sad.

Yeah. And it's crazy because as you will, you'll see, like in, uh, the other cases we talk about and stuff like, obviously every case is a little bit different, but the same kind of systemic issues are still there. And every single one of these cases.

And a lot of the, you know, police attitude is the same. And a lot of them, uh, like the one that I'm going to talk about, it's much different than like the 40 years one, because you know, her family was kind of advocating her for this person, like almost immediately, but you still see a lot of, you know, the, the attitude of the police of like, oh, they'll turn up.

You know, it's, it's fine. We're not going to like waste money to like investigate something that might not even be a missing person case. It's going to be like, you'll see a lot of the same patterns in these cases that we're going to talk about.

And I find, when it comes to like indigenous women, like I found that the police were like, oh, like, if they were like, uh, like a transient or like someone who living like in a bad situation, like maybe like the police always say like, well, maybe they're just like high on drugs or whatever.

And they don't want to be found. And I feel like that's kind of like the stereotype they get too sometimes like that type of case, but I'm just like, they're still a person, whether they're living a rough life or living like in the middle of nowhere, like they're missing somebody, their family to somebody and they're missing.

And some of you brought in the missing, like I don't know how you can just be like, oh, well they're probably just off doing drugs or whatever. They don't want to be found. Like why, who gets to make that decision? Like, I don't understand.

And I think that attitude exists, not even just in the indigenous community, but just people who are transient lifestyle, just no matter who they are.

Like, you know, people who are living on the streets, who are homeless are addicted to drugs. Like that's kind of the the police attitude for all of those cases. But I was going to say too, I think also the police like the total lack of care is kind of a self-fulfilling prophecy because they say, oh, well, there's so many missing indigenous women or so many of them, you know, turn up or they're not missing.

So we're not even going to try. But like, the reason that so many are missing is because they don't dry. So it's like, if they, maybe if they tried, when these get reported, there'd be less missing. You know what I mean? Like, it's kind of like becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Yeah, it definitely is. And I mean, nobody wants to hear like from the police.

Uh, you know, give it a week, like we're not going to start looking because they're probably going to show up. Right. I mean that nobody wants to hear that. And that Dateline episode that I had talked about earlier, um, with Jennifer Catcheway when they were saying that the, the officer was like, oh, give her a week she's probably partying that they did talk to one of the RCMP employees. And she was saying that she talked to that employee and that actually, he never said that that didn't happen. And she said that that particular officer was actually of indigenous background himself. So it's not something that he would have said.

I'm thinking like it could be true either way, like, or it could be a little bit of both, you know, maybe because he's in the indigenous community, you know, how people say, oh, you can't really be racist against your own race. So maybe it was like, oh, I'm a part of that community. It's okay. If I say something like that, you know, like we're all on the same page here, you know what I mean?

So that could have happened. He doesn't want to admit it. Or maybe the FA you know, the family's just so distraught that they got him mixed up with somebody else. Or maybe somebody else had said that they just thought, you know what I mean? So it could be both sides. A little bit of both truth on both sides. Either way, I don't think people are intentionally lying about it, but I mean, there's a whole report from the RCMP about this kind of thing.

There is a lot of internalized stigma and racism too. Like, just because you are a part of that community. You know, like you've been told a certain thing, or you perceived that behaviors so often in your own community or towards your own community. Like a lot of people internalize that and like can even become like negative about their own community or like racist or not racist, but you know what I mean? Like a lot of people internalize that and then their actions kind of go against the community too, because they're just so used to that. And then, so that is a factor too, that comes up so he could have very well said that. You know, people internalize that sort of thing. Yeah.

Yeah. That's very true. And also, also doing this research for this case, you know, a lot of indigenous people do recognize that there is an issue with alcohol and drugs and their communities. Like that's a thing that they are, you know, having to deal with and live with.

Just like with any community, there are some people that are in that lifestyle and, you know, don't want to get out. They don't want to make the effort to get out, or they're very like, you know, the world's against me, so I'm not even going to try like they have those people and of course, it's like everybody else, but just that doesn't make them, you know, worthy of not being helped when they need help.

So, yeah. There's, I think there still is a lot of racism that isn't being addressed in the RCMP and in Canada in general.

Yeah. Like, I don't want to get too technical or too, like, not academic, but like isn't there like a thing learned helplessness. Like that's a thing, like when I might be quoting, it was completely wrong.

So maybe if I am a candidate show, but isn't it like, it's a thing learned helplessness. It's like, when you, like, you learned over time. Nothing that you do is going to matter.

Well, it's like you, you can't make a difference, so why even try kind of thing.

Yeah. Yeah.

Yeah. And there are cases where some kids were taken away and they went to these residential schools for like growing up their entire lives.

And so they never were around like loving parents. So they never knew what that was like. And then they have kids of their own and they, they never learned how to be like a loving, nurturing parents, like pass that down to their kids. Maybe not abusive, but maybe some of it is like this abusive, non-nurturing, you know, non-supportive family, because that's all they knew because they grew up in this like the horrible residential school.

So that gets passed out and like these kinds of things. And so a lot of those issues, like I said, are still present in these communities.

Yeah. Like intergenerational trauma, like a lot of those issues. It's systemic issues in those communities are linked to the residential schools directly through the generations.

So the, like the alcohol or the addiction, mental health struggles in the community, like all of that is directly linked to that. And people are still dealing with that on a daily basis. And that's, like I said, the root of a lot of those issues. So you have to kind of get to the root of the issue. You have to acknowledge the trauma has happened and you have to learn how to deal with it and move on and heal.

And then the other issues that come from that. It'll be easier to solve those issues.

Yeah, exactly. Like you think of people that lived through that. And now they're adults. They have to deal with this somehow. Like that's how they deal with it as like this alcohol and drugs, or as a, they maybe didn't go to the schools themselves, but they had children that did, and those kids just never came back.

Like, how do you get over that? You don't, there's no help from the government. So a lot of people turn to drugs and alcohol because of that. Like they have nowhere else to go and just, you know, so it really, really is, did all stem from these residential schools, which obviously was a big, you know, obviously, it was a big mistake and there's no way for us to like, fix it except for offering them support now that's really what we can do. So, yeah.

Yeah. And just a little callback to our interview with Amy Bryant when she said trauma is the gateway drug versus any, um, like substance itself, like it all, a lot of it starts with trauma. So once you know, that leads to a lot of these addictions and other issues.

It's very present in the indigenous community, for sure. And like over a century, like 150 years, these schools were open. So can you imagine how much distrust these communities probably still have with the government and, you know, with law enforcement, because of, you know, they're the ones that did this to them.

So we can totally understand this, like disconnect in this. I don't want anything to do with the government. And that's why a lot, like there's still all these remote reserves away from the cities and it's just like, yeah, it's a big, like a lot of them don't even have like clean running water. I mean, that's like the government should get on that.

Like where's the government, like when these communities need water, like, you know, so there's, there's still a lot that government could be doing that they're not yeah.

Like some community that's still under a boil water advisory. They have been for decades. Who you, when you think of Canada, you think of, you know, it's a pretty, you know, wealthy country.

Yeah. Uh, I mean, at this point, everyone should have access to clean running water. Like there really is no excuse, except for the government does not give two shits. That's all it is.

Yeah. And some politicians pretend to care when they need your vote and then completely bail on those issues later. That's I against whatever, I'm not going to get in political, but you, you, those of you listening know who I'm talking about. So if you're Canadian, you do.

We just had another $600 million election for an outcome that was exact same as it was like where'd that $600 million could have went to, you know, clean water for indigenous communities. Like fucking start there and not do a whole new election. Yeah. Just do something good with your money, please, for once..

Yeah. That's our little PSA, I guess, we're fresh off an election guys. This is how, this is how we're feeling. So.

Yeah, it's awful. There's still a lot, a lot of work to be done and;

Yeah. I mean, that's as good episode to kind of kick off our mini series. Like you said, cause like Tina Fontaine, you know, murder and everything kind of ignited it on like a wide spread level.

Like it was always, I think obviously like there were people who were advocating for the community and stuff. Long time before that, but that was what really brought it to like the public, the wide public consciousness. So it's a good way to like start off the mini-series, as we say, because how we can tell a lot of other stories and some of the stories happened, obviously, it was the spirits before Tina Fontaine's murder, but.

We could have a whole series of just cases of indigenous women.

I mean, yeah, we could have like a whole season of it there's but the thing is like, you couldn't have, you know, more than one or two episodes about one person you'd have to. You know what I mean? Cause there's so little about each person.

Yeah. Which is unfortunate because there's like nothing out there on, probably half of the people that are missing or murdered.

Yeah. So stick around for the next couple of weeks to learn more about missing and murdered indigenous women in Canada, we will see you next week

Stay tuned for part two. We'll see you next week for part two.

You can find us on Facebook at Crime Family Podcast on Instagram at Crime Family Podcast. We also have a Twitter Crime Family Pod 1. And also if you have any case suggestions or any tips or tricks to the podcasting world, you can email us at crimefamilypodcast@gmail.com

so we really love hearing from you and hope to continue to do so. Okay. See you next time. Bye.

Bye.